The Private Secretary

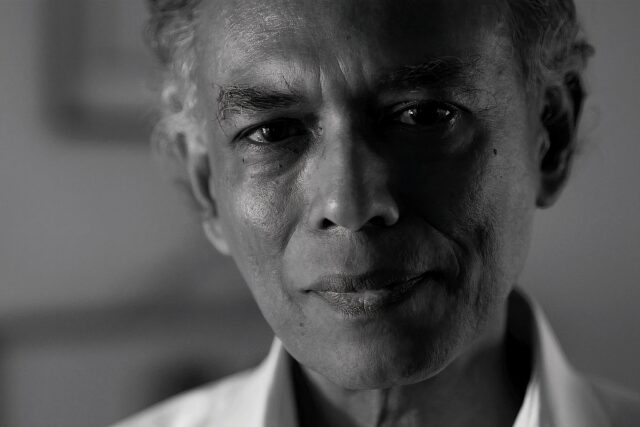

Parakrama Dahanayake

Parakrama Dahanayake reflects on growing up in the political shadow of his uncle, former Prime Minister Wijeyananda Dahanayake. Having served for years as his uncle’s private secretary, he recalls a life shaped by politics and explains why he eventually decided to enter public life himself.

We arranged to meet Parakrama Dahanayake at his office in the old kachcheri building inside Galle Fort, where he was working as chairman of the Galle Heritage Foundation. The building was undergoing restoration and we climbed a dusty staircase to reach his office.

Within moments of introducing ourselves, Mr Dahanayake began recounting the life of his uncle, Dr Wijeyananda Dahanayake — former prime minister and one of the south’s most colourful political figures. His recall of dates and details from his uncle’s long career was remarkable. It felt almost rehearsed, as though he had told this story many times before.

But I was interested in the nephew.

I suggested we continue the interview at the family home. When we arrived, it became clear why the uncle’s story came so easily. The front room had become almost a shrine. Photographs and memorabilia filled the walls and shelves. A large portrait of the former prime minister rested against the wall because there was no space left to hang it.

“This house was always open,” Mr Dahanayake said as he showed me around.

He then introduced me to his elder brother, a former mayor of Galle, who was sitting quietly in a room at the back of the house with a small radio beside him. Despite having lost his sight to a congenital condition, he had continued to serve as mayor.

Mr Dahanayake seemed convinced that I had come to speak with his brother. When I explained that I was really there to interview him, the elder brother laughed and called out down the hallway:

“He’s come to speak to you, Parakrama, not me.”

At that moment it became clear that the house was not the best place for the interview. Too many other lives — and reputations — filled the space.

We returned to the Foundation office and began again. Slowly, as we spoke about his own work and his decision to enter local politics later in life, Mr Dahanayake finally stepped out from behind the long shadow of his uncle.

Galle

November 25, 2010

Transcript and translations

Language

Subjects discussed

Fortunately or unfortunately, I was born into that family

My late uncle, Dr Wijeyanantha Dahanayaka, was perhaps for about fifty years the pivotal political character in Galle. Not only in Galle, but maybe the whole of the south. I was fortunately or unfortunately… (Laughter) I was born into that family and I was part of that house. And I also became part of his political life.

It almost came automatically. I started helping him with the secretarial work and also with some of the organisational work in the electorate.

He was a unique person. Because on the one side, he never went after any acquisition of wealth or any personal benefits. He was more or less totally dedicated to serving the people. During that time, there were a lot of cases, where senior politicians used to groom their children, their family members to put them into political positions. But my uncle never wanted to do that (Laughter).

I must be honest here. There were times that I also felt that I should also have a better deal from him. There was a time, that was later, when he was Minister of Cooperatives. I was his private secretary again. During that time, all the private secretaries of cabinet ministers at that time had government vehicles allocated to them. I did not have (Laughter). I asked the ministry secretary then, why I am not given a vehicle. So he said, “Well, the thing is we talked to the minister and he was not very keen on giving you a vehicle”. (Laughter). It was his way.

Even after his retirement from politics. I was very close to him. I was looking after him even when he was hospitalised after a fall. You can say I miss him, but of course he lived a full life. He was ninety-four when he died. And I am very happy and very proud that I was part of his life and I was able to help him in various ways.

Comments

Leave a comment