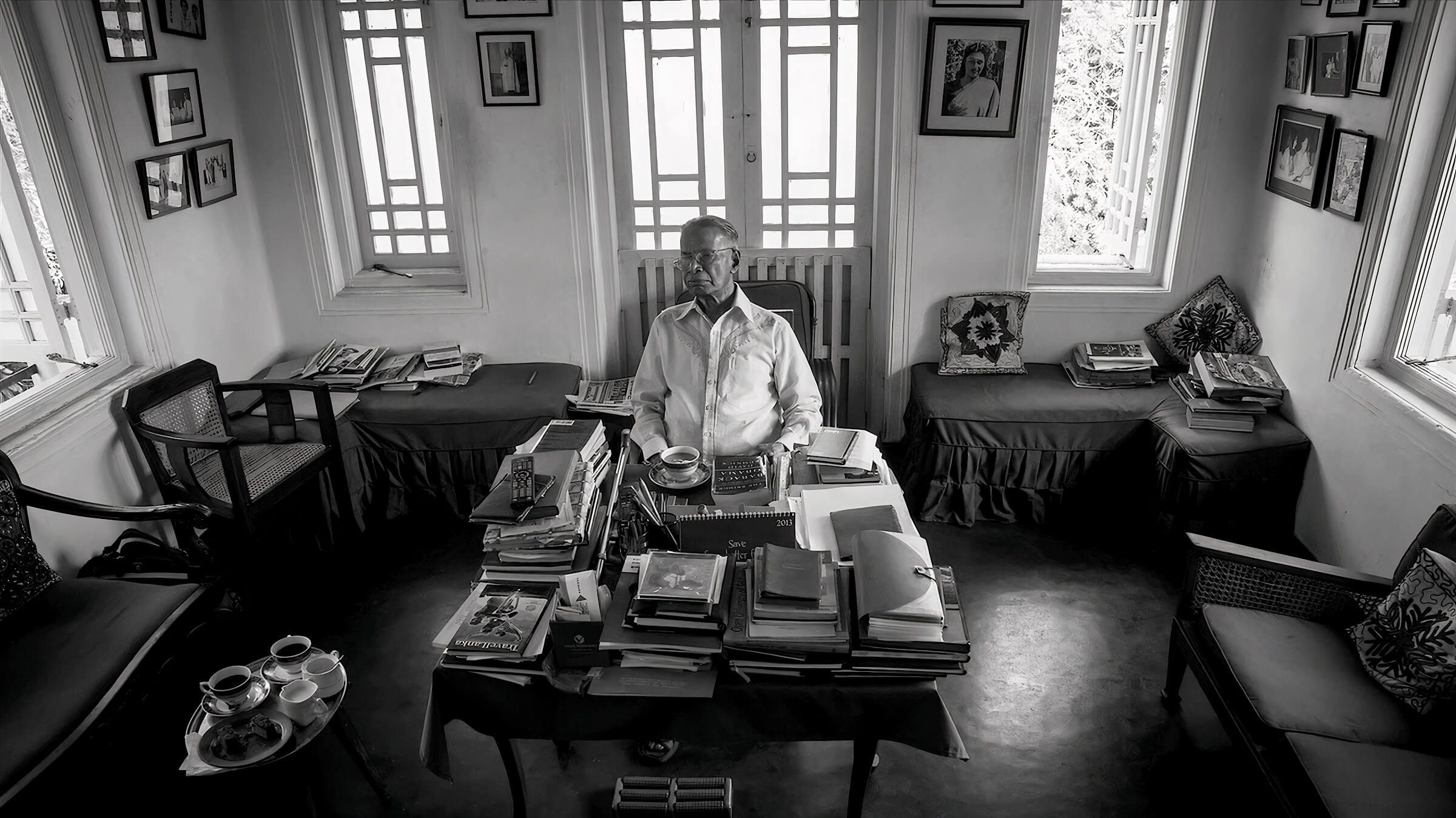

The educator

Sam Wijesinghe

Sam Wijesinha has had several careers from criminal lawyer to Chancellor of The Open University. As President of the Prisoners’ Welfare Association, he focused on reforms to better the lives of prisoners and their families. His commitment to education extended not only to helping his poor relatives but the children of junior staff when Secretary General of Parliament.

Transcript and translations

Language

Subjects discussed

I haven’t forgotten my beginnings. I’m from the village

No, No, I’ll sit at the head of the table.

This is where I sit for meals.

Rukman? Can you bring a cushion for the chair. And my other pair of glasses.

You know, there’s a Sinhala line…poem.

(Sinhala). The cause of ignorance is not receiving education.

(Sinhala). You are pining for a job because you haven’t got a job.

(Sinhala). The cause of sickness is the greed for food.

(Sinhala). If you forget your beginnings, you will be a poor man.

So I haven’t forgotten my beginnings. I’m from the village, I am not a Colombo Seven man. Some people treat you big, but I say I have poor relations. Tell me the man who hasn’t got poor relations? And my job is to see that they get educated. Not to discard them and say they are not my relations.

I have brought up a lot of my relations — one family and nine doctors. Not that I spend for all of them, I help them. By paying their fees. I never say I will do everything because you never give free everything they lose. Pay part of it.

(Telephone rings)

No news yet. You don’t get worried. You just wait patiently, till I do it. I know you are anxious, but your anxiety cannot be transferred to me. So don’t worry.

Well, in Parliament I found a lot of printed material in both Sinhala, English and Tamil. Printed in the separate department…in the government printers for Parliament. But the members don’t read. Very few people read. I collected all this. At the end of one year, I had about a million rupees by selling thrown up paper. I thought, this is money. So I took it and I used this to buy books for the minor staff. Unheard of thing.

And I put books into the library for the minor staff to read and do the O levels and the A levels. So the minor staff used these things and got through exams and did well and their children were educated with the money. And when I left Parliament after 18 years, there were six boys of the minor staff who were doctors. Something they never thought of…at the beginning they did not know any English but the clever boys get into medical faculty. At the end of the five years, they’re jabbering away in English. I come from the village. There are a lot of poor people. I know their problems. So that’s why I took this out and a lot of poor people from the villages whose children are peons, learnt. You know, I have seen the class difference in the villages. We were the wallawa people and the other people were the farmers, who did our paddy fields, worked on our plantation. And there was a tom tom beater caste boy, who came bare-bodied. And he used to sit by my chair, on a small stool. And I learned arithmetic from that fellow. I am here and that fellow must be doing the drumming someplace. Like that. And I have seen how they live.

My father used to pay 40 cents for a man and 20 cents for a woman in the 1920s. But he was a very good hearted old gentleman and he told me one day, “Son, when you are big, don’t think of doctoring and lawyering and all that. First of all, grow up to be a gentleman.” (Telephone rings).

Comments

Leave a comment